Being a homeowner is a full-time job. It’s something that requires a great deal of attention, patience and care – not to mention upkeep. Yet, beyond the malfunctioning water softener or the leaky kitchen faucet, there are myriad external factors (and creatures) that can affect the overall longevity of your home. We’ll focus on two types we know best: bees and wasps.

What Types of Bees Are There?

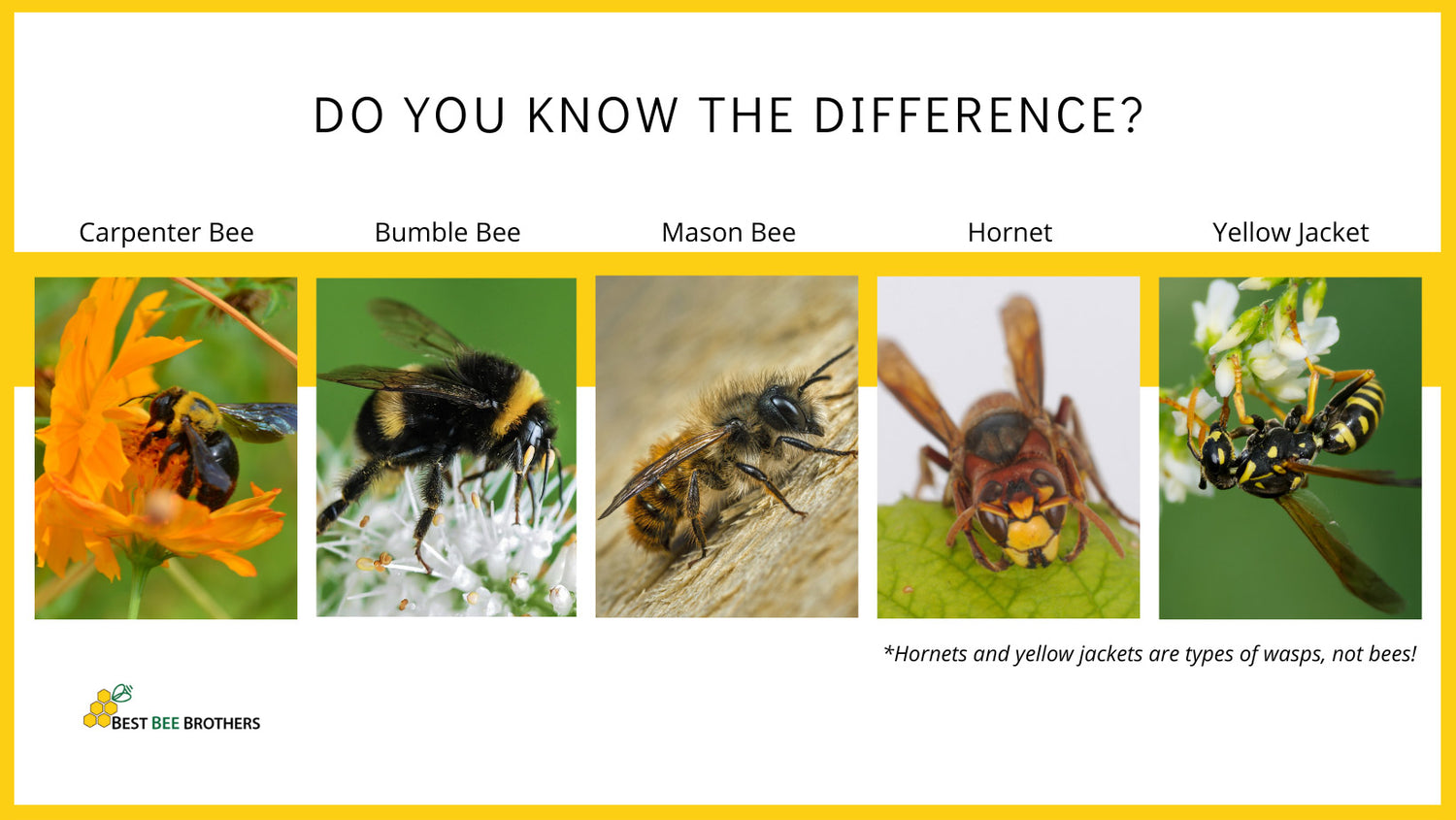

There are over 4,000 species of bees native to North America1, so keeping track of the good guys (the powerful pollinators) and their not-so-desirable counterparts (murder hornets?!) can be difficult. To help you keep it all straight, we’ve compiled a list of some of the most common critters you can expect to see at your next backyard get-together.

Carpenter Bees

Effective wood drillers – much to the chagrin of unlucky homeowners – carpenter bees are solitary bees, typically living in units of a single male and single female carpenter bee. Their nests are typically found in the roofing, siding or exterior paneling of homes or in other untreated wooden surfaces, which the female drills into to make her home. Like other bee species, the carpenter bees prefer to wait out the cold winter weather by hibernating in their nests. Come spring, however, both the male and the female carpenter bees emerge and begin the busy work ahead of them.

For the female carpenter bees, this means constructing or repairing a nest and laying her eggs. Male carpenter bees, on the other hand, have only one significant role to play in the family dynamic: protector. While male carpenter bees cannot sting, they can be highly aggressive and territorial when defending their nest. It’s generally the male that has the most interactions with humans, dive-bombing any would-be intruders that are too close for his liking.

Eastern carpenter bees generally resemble large bumblebees and can often be mistaken for them, but you can tell them apart by their smooth blackish-blue-colored abdomen. The thorax is where the common yellow, orange and white hairs are, along with dark thick hair on the legs. Carpenter bees can range from ¾ to 1 inch (about 2 to 2½ cm) in length. Female eastern carpenter bees (Xylocopa virginica) have pure black heads that can easily distinguish them from males, with distinct white markings. The valley carpenter bee (Xylocopa varipuncta), however, found in the Southwest and in California, looks quite different. The male is golden, with hairy legs and a green tinge to its eyes.

Mason Bees

Unlike their more notorious cousin the carpenter bee, mason bees are generally welcomed in the suburban backyard. Their gentle nature means they seldom ever sting, even if provoked. And while the females do have stingers (male mason bees, like male carpenter bees, do not), a mason bee “attack” is said to be much less painful than other types of bee stings.

In terms of diversity, mason bees make up a large segment of native North American bee species2. For this discussion, however, when we talk about mason bees, we’ll refer just to the North American mason bee – one of some 140 different species all classified under the mason bee mantle.

In terms of habit and lifestyle, mason bees are often compared with carpenter bees due to their solitary nature. Unlike other species, mason bees do not live in colonies or hives, but rather create small units or families of other mason bees that nest together through the winter. Male mason bees are not nearly as hardworking and industrious as their female counterparts. Female mason bees are incredibly beneficial to an ecosystem. Some estimates maintain that a single female can pollinate over 2,000 plants a day!3

North American mason bees also look quite distinct. Instead of yellow-and-black stripes, these little pollinators have a metallic blue, black, or green iridescent shine and are covered in a healthy layer of fuzz. Physically, the mason bee is also much smaller than the carpenter bee (with the females being even smaller than the males), with an abdomen that is typically ¼ to ½ inch in diameter.

Hornets

When it comes to an intimidating insect presence, the hornet is right up there with some of the other power players in the animal kingdom. Interestingly, hornets are not bees but are wasps of the genus Vespa, closely related to (and resembling) yellow jackets4. That’s right; hornets are a subspecies under the overarching term “wasp”!

Unlike mason or carpenter bees, the hornet is not a solitary creature but lives in the traditional, aboveground nest. The queen governs life inside the nest and dominates the general activity of the workers. She is also the only female to produce offspring in the entire hive; other hornets are generally asexual female workers that work to serve the general good of the colony by gathering food, maintaining the hive and protecting the queen. Males – much fewer in number – play a considerably limited and specific role in the hive. The primary function of the male hornet is to cohabitate with the queen and produce more offspring. Unfortunately for them, the life of a male hornet typically comes to an end soon after his sexual union with her.

The typical hornets’ nest is composed of chewed-up wood pulp, which is turned into a sticky paste. Hornets’ nests are typically very large, and can be found hanging from sturdy tree branches, eaves and decks. Like other colonies, the hornets’ nest is a source of endless activity, with workers coming and going all day long. While considered not unduly aggressive, hornets are territorial and will defend their nests if they feel threatened. When it comes to stinging, the good news is that male hornets cannot harm you – only the females have that ability. The bad news, however, is that unlike bees, female hornets can sting repeatedly and painfully.

Yellow Jackets

Like hornets, yellow jackets are a type of wasp, and they are distinguished by their opaque, smooth, yellow-and-black-striped bodies and slender abdomens. Similar to hornets, yellow jacket hives consist of a queen, called the foundress, as well as male and female workers. In fact, the yellow jacket shares many characteristics with its not-so-distant relative, including the female’s unfortunate capacity to sting multiple times.

One interesting defense mechanism of the yellow jacket is what happens to it post-mortem. As sort of a desperate, final call to action, the dying yellow jacket releases a pheromone that acts as an olfactory alarm to all other yellow jackets in the area5. This potent scent mobilizes the remaining members of the hive, and can produce an immediate and intimidating response: Attack!

Hornets and yellow jackets aren’t just famous for their powerful stings though. Another distinguishing characteristic of both is their proclivity – especially as larvae6 – to eat meat! That’s right, both hornets and yellow jackets are capable of digesting meat for its protein. Young yellow jackets are often fed soft-bodied insects, leftover scraps from garbage pails or portions of dead animals. Unfortunately, this fact only increases the likelihood of yellow jacket encounters with humans, since the responsible yellow jacket parent will be out and about searching for scraps for their young. For more information about how to get rid of wasps near your home, read our post “When Is Wasp Season?”

How to Get Rid of Different Bees at Your House

Given the large variety of bees and wasps out there, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach to ridding your home of unwanted intruders. That being said, it’s important to understand that not all bees are dangerous or damaging to your home. Mason bees, for instance, are simply opportunists that prefer to nest in existing structures, but will not bore tunnels into your home to do so (unlike the pesky carpenter bee). As a result, they pose no real threat to you or your family and may not always need to be removed. Some people want them around because of their pollinating abilities, and our Bee Lodges are designed to house mason bees around your home.

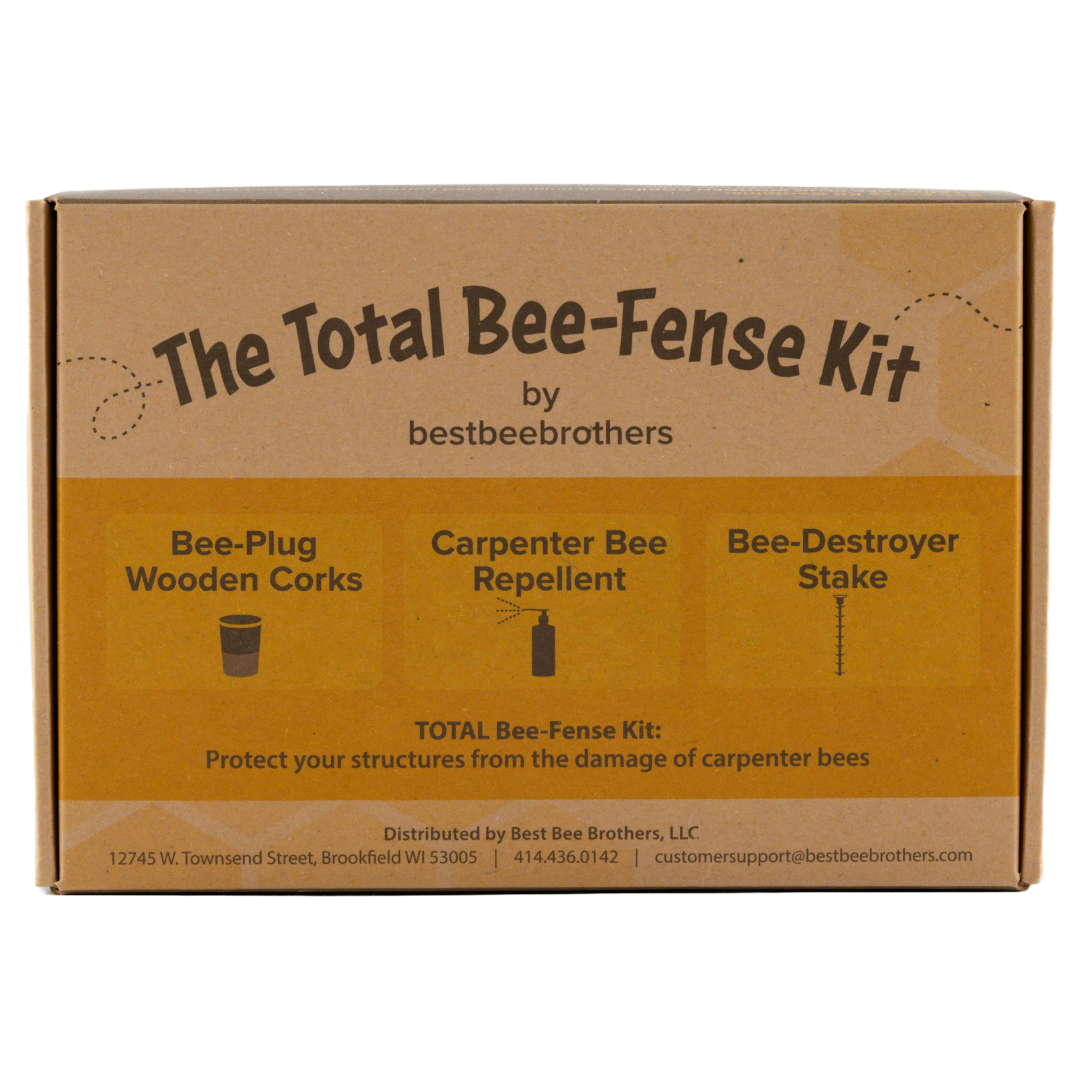

In contrast, wasps (both hornets and yellow jackets) can be highly territorial. Individuals who are allergic to their venom should be especially careful, as it can sometimes necessitate a hospital visit if stung. Given these creatures’ hive mentality and sheer numbers, it’s not a good idea to attempt to disturb a yellow jacket or hornets’ nest on your own. Instead, we recommend using passive traps or other discouraging mechanisms to keep you safely out of harm's way. Our Wasp Deterrent is a great example of capitalizing on species behavior. Since wasps don’t often want to nest near other existing hives, a decoy is often enough to keep a new nest from appearing. Similarly, our Carpenter Bee Trap is specifically designed with this creature’s behavioral characteristics in mind, to effectively lure and trap destructive carpenter bees from wreaking havoc on your home.

So when should you start? In general, early spring is the best time to begin fortifying your home. When it comes to carpenter and mason bees, plugging any existing nests can be an effective way to get ahead of the problem (see our Hand-Dipped Wooden Corks). Similarly, since nearly all wasps except the queen die during the winter months, knocking down any remaining yellow jacket or hornets’ nests before she begins her mating season is much less troublesome than doing so when things are in full swing. If you notice a large (sometimes basketball-size) nest, chances are it’s probably teeming with brightly colored hornets and yellow jackets. At this point, you may want to call a professional rather than attempt to handle removal on your own.

- “How Many Species of Native Bees Are in the United States?,” USGS, U.S. Department of the Interior, accessed January 26, 2023, https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/how-many-species-native-bees-are-united-states?qt-news_science_products=0#qt-news_science_products.

- Bruce E. Young, Dale F. Schweitzer, Nicole A. Sears and Margaret F. Ormes, Conservation and Management of North American Mason Bees (Arlington, VA: NatureServe, 2015), 1.

- Carol Koenig, “Mason Bees,” The Real Dirt Blog, Regents of the University of California, March 3, 2017, https://ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=23425.

- “Hornets,” National Geographic, accessed January 26, 2023, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/facts/hornets.

- Joanne Spencer, “Yellow Jacket Wasp,” Animal Corner, November 7, 2022, https://animalcorner.org/animals/yellow-jacket-wasp/.

- “Everything You Need to Know About Yellowjackets,” PestWorld.org, National Pest Management Association, accessed December 31, 2022, https://www.pestworld.org/news-hub/pest-articles/everything-you-need-to-know-about-yellowjackets/.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.